Siege: A short story

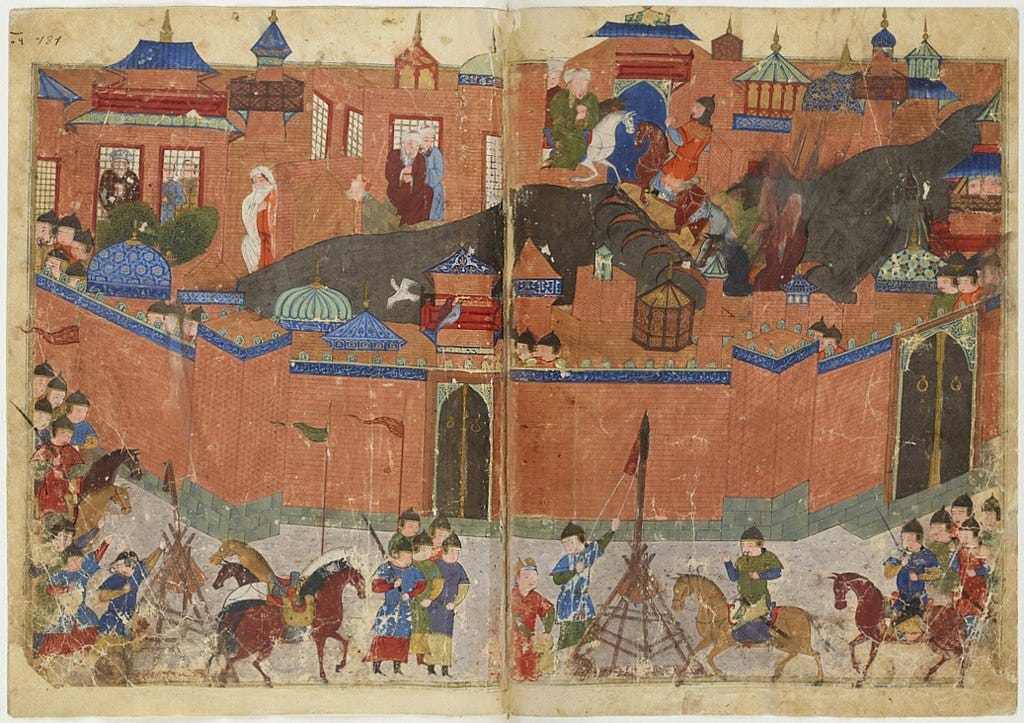

This Substack's tentative foray into fiction - a silly tale about a medieval castle under siege from a Mongol horde - which speaks to my current feeling of dread.

Kia ora,

I don’t know about you, but recently I have been waking each day with a grim feeling of dread weighing deep upon my bones.

The politics. The weather. The world. It is all a bit much.

My one escape has been to read.

I have been plowing through fiction like a plow through a plow-field. It has been cathartic to let my heart fall and rise against these fictional worlds, and has reminded me that before music, or performing, my first love of art was and remains stories and storytelling.

Some people might not know that I studied creative writing quite seriously before releasing music as D.C. Maxwell. I went to the loftily named but fairly chill International Institute of Modern Letters in Wellington and also the Creative Writing Programme at UCLA.

During my studies I wrote many short stories and one terrible novel half-based on my tango with the dark underbelly with some of the grim cretins that fund high art in New Zealand. Now that I am writing and releasing music, my fiction writing has slowed down.

But a while back this story kind of fell out of me, and I have been wondering what to do with it.

So I thought I would share it with you lovely people on D.C. Dispatches as it seems to express a lot of things I am feeling at the moment, about the danger of a slow contagion of dread taking hold.

The story is set in a medieval castle under siege. I’m quite happy with it and I would love it if you could let me know what you think in the comments!

Love,

D.C.

Siege

On the twelfth week of the siege the Tatars ran out of severed heads and began catapulting chickens over the ramparts. They sailed against the sky in a hail of squawking feathers and landed on the cobblestones with a thud. Most of the chickens died on impact, but some survived the landing to twitch lamely or to run about with the fervour of a herald with some urgent task.

The besieged fell upon the chickens with a single minded ravenousness. The Tatars had covered the fowl in excrement and grime, but many were too hungry to care. Despite stern warnings from the Keeper of Records, many ate of the chickens and in the following days became red of face, cold of heart, and died with much retching and bile. In this way our small number was greatly reduced.

After the man who previously held the job perished to the poisoned fowl, it suddenly fell upon me to communicate with the Tatars. Our initial negotiator had succumbed to helplessness and thrown himself from the wall, survived, and allowed the Tatars much fun trampling his corpse before the gates. After him a series of heralds had taken up the role, but died in a variety of ways too numerous to list.

So it came to me, a humble baker, to make peace with the Tatars before we all died of starvation.

The Keeper of Records estimated I had seven days.

Day 1

The Tatars were assisted in their communication by my cousin, Dmitri, a farrier who had surrendered himself to the Tatars long before our gates had even closed.

I had not previously been very fond of Dmitri. He found many occasions to talk at length about a new kind of horse he imagined breeding, with skin like a lizard and feet like a fox - a foolish prospect. He was also extremely adept at calculating his arrival and departure times from the tavern to imbibe in the maximum rounds of ale with the minimum of payment. But despite these peevish habits, I had not expected him to side with the smelly wild men that now surrounded our castle, or to do it so willingly.

“Did you like the chickens?” Dmitri yelled up to me on the castle wall.

“No,” I yelled back.

Dmitri explained my response to the Tatar riders slouched on horseback behind him. He made great play with my simple answer, flapping his arms to represent the chickens, running about wide-eyed to represent the hungry inhabitants of the castle, and gambolled like a drunk before he keeled over to represent the sick and the dead.

During this show there was a roar of laughter from the Tatar mob. Some reared up their horses in a showboating manner to make it seem as if their steeds also found joy in Dmitri’s story, which I highly doubted possible.

One Tatar more truncated than the rest, who wore a large Turkish cap, grunted at Dmitri in his foul guttural tongue. Dmitri cocked his head as if hearing a lover’s poetry, then turned back to me.

“They say: open the gates and they will let you live!” He yelled.

“Piss off! Go Away!” I yelled.

If any reading this chronicle find my words foolish, note this: After weeks of being barraged by the severed heads of our countrymen, I found it highly improbable the Tatar host had suddenly found clemency. I gave Dmitri’s words as much faith as if they were spoken by the serpent itself.

Dmitri conveyed my reply to the Tatars, again aping comedy of our grim plight.

This time there was no laughter. Instead, the be-hatted Tatar raised his hand, and from the mass of stinking foreigners surrounding our keep came a storm of arrows.

I stood a moment to witness the arrow-storm’s near-blotting of the sun (a novel sight, even when intended to kill thee) before I stepped into an alcove to wait out the barrage.

Day 2

In the morning I met with Karl, the last of our noted fighting men. Though only a common soldier in peacetime, the death of every other reasonable candidate had made him the de facto leader of our pitiful resistance.

Karl had come up with many clever ploys to try and get us out of this mess; such as forcing the remaining women and children to clank pots and pans to make it seem the blacksmith was still in operation; or pressing the Bugler to play eerie tones in the dead of night to frighten the besiegers. While innovative, unfortunately none of his ideas had so far worked.

Karl had been struck in both legs by arrows during the eighth week of siege, so these meetings took place in an empty stable where he lay seething with rage and gangrene.

“You spoke well yesterday,” he grunted.

“Thanks,” I said.

“You were a real firebrand. A voice I am proud to hear speak for us.”

I nodded and tried not to look at his legs melting into sludge in the dirty hay.

“Is that pintel-headed whoreson still with them? Or have they eaten him?”

He meant Dmitri, my cousin.

“He’s still there, and if they have eaten him the only part they touched was his brains,” I said.

Karl emitted a strange wheezing laughter while his face remained as rigid as a death mask.

“Dmitri will burn in eternal damnation for his betrayal…” said Karl, before taking a deep breath.

One of Karl’s favourite topics was the different devilish punishments that awaited Dmitri in the afterlife. I leant against the stall’s entrance and waited out the long speech.

It was strange to converse with a man who in normal days would make jest of riding his horse into my market stall and knocking down my breadbaskets. But these were not normal days.

Karl wrapped up his hellish predictions for Dmitri and launched into today’s negotiation strategy.

“Try to talk directly to the fella with the funny hat. Tell them our neighbours over the hill have beautiful women and lots of gold and they should go there. But don’t say it to Dmitri, say it to the hat-man. He can understand us, I think.”

Later, peeking over the parapet, I saw the army had shifted during the night. The Tatar soldiers rode six horses to a man and had churned our surrounding fields to a dark sludge of ripped earth and horseshite. The army was encamped on a distant hill and shadowed the grounds like hives upon a plague victim. Only five Tatar riders remained below the castle walls, and Dmitri, who squatted near their horses, thoroughly goat-like.

At a grunt from the behatted man Dmitri scurried toward me on the wall. There was a gleeful glint in his eyes as if he was delivering a happy and mirthful message. This was a man that had drank of my mead and danced with me for hours. That had wiped my face when the mead sickness took hold. That had let me sleep in his hut when my wife had become furious at both the mead-sickness and the loud and boisterous dancing.

To see him now, not just working with devils that catapulted severed heads and diseased chickens, but to actually seem to enjoy doing it, was not so much saddening, as mystifying.

When he came within throwing distance, I managed to launch a decent sized rock at his head which knocked him on his behind.

The Tatars laughed heartily. Some on the hill raised their arms mirthfully to show that, even at this great distance, they had seen Dmitri hit on the head with the rock.

With a sour scowl, Dmitri warily approached the castle wall.

“Don’t throw any more rocks while we are talking,” he said.

“I’ll do what I want, you traitorous whoreson,” I said.

“If my mother is a whore, that makes you a whore’s nephew, cousin!”

In response I made to throw my hand, but it was only in jest as no stone was contained within it. Dmitri dove foolishly into the muck to avoid the phantom stone, and the Tatars behind him chuckled with rhythmic menace.

“Quit your foolish resistance! You will only be met with death!” Dmitri yelled, rubbing mud from his face.

His voice was a strange whine that had grated me even before the siege, when he had lambasted the price of cheese, or spent long hours speaking to the various uses of his future horse-fox. But under the current situation his voice made me truly sick.

“Let me speak with the Tatar king,” I said.

This seemed truly to stump him. Dmitri shifted from foot to foot, uncertain how to reply.

“He does not speak our tongue,” He yelled.

I, ready for such a forked response retorted, “And I do not speak the tongue of a traitorous devil, so your words are nothing more than the bleating of goats to me. Fetch the Tatar!”

Dmitri reluctantly scampered back to the Tatars who were horsebound and solemn. He spoke for some time, making great gestures of idiotic clowning. But there was no laughter. The Tatars looked up at the castle, then rode hard back to their encampment.

Without fear of arrow-fire, I stood upon the battlement and watched Dmitri scuttle horseless and browbeaten in their wake.

Day 3

The Keeper of Records emerged from the turret-nook he had holed up in to inform me there was not a scrap of food left in the entire castle. I took this to mean that the provisions the greedy monk had hoarded for himself had run dry. While this was true, it did not change the fact that many were starving. Some even made plaintive cries skyward for more of the cursed chickens to fall.

Though these were my kinfolk, I was growing tired of the whining calamity. The only one who had not seemed to have lost hope was Karl.

While his body disintegrated, his mirth floweth over. At my approach he beset to giggling.

“Hah! I believe Dmitri will think twice before heralding the devil's messages over these walls!” he said.

While Karl positively cackled with joy, I cannot say I felt the same. To see our proud soldier, (even one I did not particularly like) with legs blackened and leaking, with teeth falling from withered gums, was not an inspiring sight.

“Did you ask for the Tatar king?” He said.

“I did, but I have not spoken to him,” I said.

“When you speak to him, tell him of our God, who art mighty and vengeful, who remembers the deeds of this life for a millennia of hellfire.” He began to wheeze with religious exertion. “Tell him that Dmitri has already fallen from favour of this God, but it is not too late for the Tatars. If they leave us be, and go to our neighbours over the ridge, who are much richer, and have much more beautiful women, they will be saved.”

Karl sank into the hay. The stables, empty of horses from an ill fated cavalry charge in the second week of the siege, rang silent with his ragged breath.

Up on the ramparts I saw that the Tatar army had now completely disappeared from view. Only the five Tatars and Dmitri remained in the mud below the walls. There was no sense of relief, something in the trembling air said the army remained primed to descend at a moment's notice.

Dmitri sauntered delicately towards the castle and stopped just short of a stone’s throw.

“The Tatar will see you now,” he yelled.

The behatted Tatar and his retinue trotted forward. They sat solid and proud upon their horses with faces still and frightening as wicked devils in a carved frontispiece. Most impressive to me was the behatted Tatar’s horse, which short and stout as its master, stood with such muscular ferocity that I wondered if it was fed on grass or flesh.

To my surprise the Tatar spoke.

“Hello,” he said. In a gruff, guttural voice that bounced off the ramparts.

“Hello,” I replied.

The Tatar seemed pleased with this and turned to his friends with more of his native grunting, which provoked much laughter, including from Dmitri, who I could tell did not know what was being said.

Then the Tatar yelled something else.

“What?” I cried, making large motions to convey my lack of understanding.

The Tatar spoke again. I just shrugged.

Dmitri attempted to intervene but the Tatar and his retinue turned and galloped over the ridge, trailed by my hapless cousin.

In their wake I yelled Karl’s religious message, but it was pissing in the wind for all it helped our cause. The skies remained blue, their horses trotted on, and my words fell helpless in the muck.

Day 4

Balár, one of the last 10 men, had to be executed after he was caught eating the flesh of his dead wife. I was sad to see him go. He was always with a kind word as I paced the ramparts under darkness trying to figure a way out of this mess. But it’s one thing to grumble and gripe in a comradely way, it’s another to eat the flesh of your dead wife.

We buried fifteen others. None had the energy, nor the space to dig a grave, so our burying consisted of tipping their bodies into the ravine behind the rear wall.

The Tatars did not appear before the walls on this day. The watch kept an eye on the ridgeline but none were seen except for a lone figure on foot who several times peeked at the castle before disappearing.

Karl slept. Many people bothered me with complaints. It rained.

All around a grim day.

Day 5

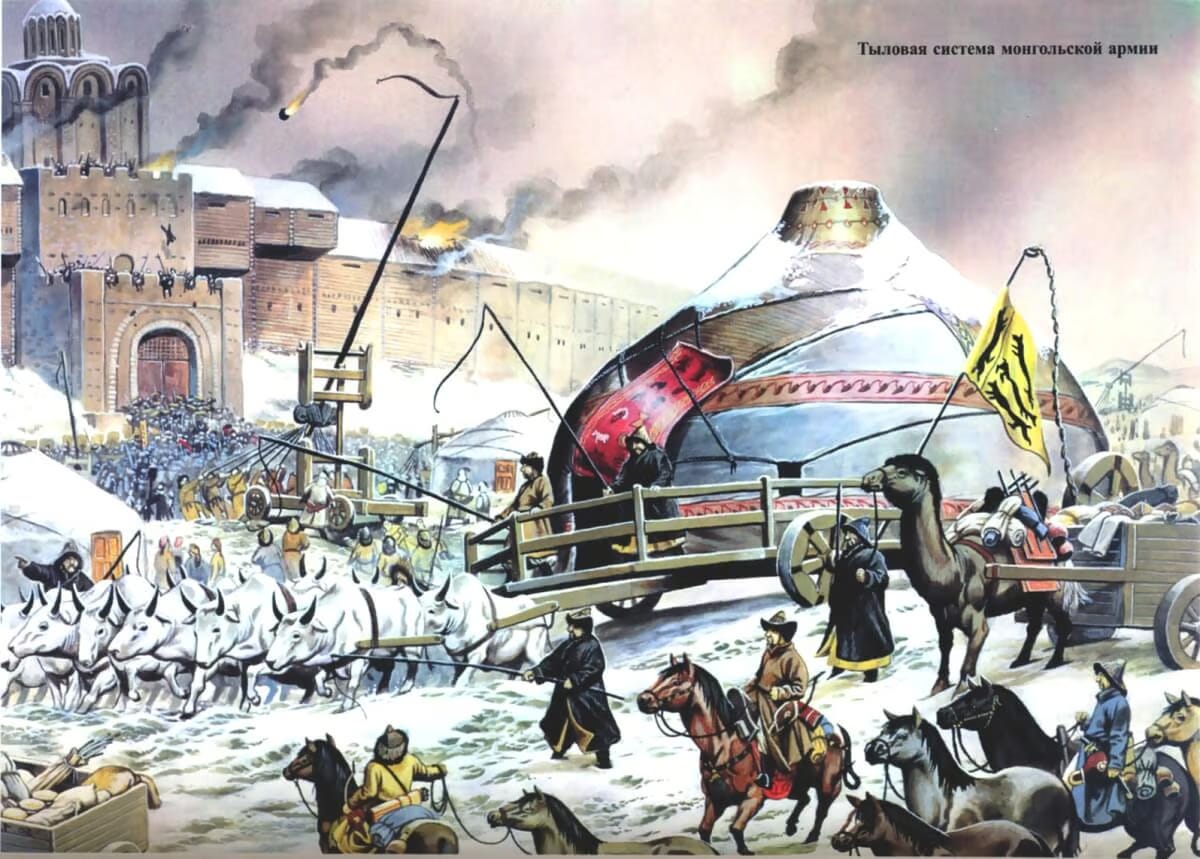

The Tatars returned and brought with them many siege engines which struck terror into the hearts of all that saw them. Great towers beset upon large carts rolled across earth. They bristled with grinning archers smiling as if their quarry were as much fun as a hobby horse. In addition to the towers came a great battering ram tipped with an iron boar, and large trebuchets that trembled in anticipation of launching hellfire upon us.

The Tatars had more men than could be counted, and more horses than even that. Where in previous weeks their army had raised bedlam with their hoarse brute songs, today they were largely silent. The wind blew their sour horsemilk stench toward us like a curse.

The army and its engines came to rest a short distance from the castle walls. The be-hatted Tatar rode up and Dmitri followed on foot. Dmitri had been given a leather breastplate in the plaited style of the invaders, but it was far too small for him. He looked ridiculous compared to the proud Tatars. But I could tell by his grin that he thought himself the finder of a lucky coin or some other childish fancy.

The behatted Tatar looked tired, his shoulders were low and his head slumped forward. To see him was to think that the power of the horde behind him was more burden than a blessing.

The Tatar spoke.

“I... do... not... like... this...” he said in a slow and stilted manner of an altarboy stumbling through his latin.

“Then just go away!” I called down.

Dmitri made to convey my message but the Tatar gruffly waved him away.

“Look...” he said, waving dismissively at the army behind him. “We... spend... many days... this place... we must... breach.. your walls.”

As a baker, many a morning I had kneaded and proved and kneaded and proved only for the bread not to rise. But the cost of time and ingredients meant I was forced to bake it anyway and try to palm it off to some fool who did not know bread from horseshite. So I could understand the Tatar’s logic, even if I did not like its outcome.

The Tatar grunted towards Dmitri, who had become bored with the exchange and was inspecting a clod of dirt before him.

“How many of you are left in there?” Dmitri yelled.

I thought upon the dozen or so emaciated wastrels that straggled through the empty castle. “As many as 300! All are brimming with bloodlust and begging someone to attempt these walls so they can fall upon them with steel and the gnashing of teeth!” I yelled heartily.

The Tatar smiled wearily. “I... am... tired...” he said. Then parlayed a long series of grunts to Dmitri and rode away.

“Cousin, listen closely-” Dmitri yelled.

“You are no cousin of mine, you traitorous pig!”

“Cousin - you have two options. Firstly - these men could breach the castle walls, then kill everyone inside. Or secondly - these men could walk through the castle gate, then kill everyone inside, except for you.”

To see my own flesh and blood, so blasé to pass such a grim ultimatum on his own people left me thoroughly vexed to say the least.

“I never liked you! I think you are a terrible dancer and - and - I’m glad your mother is dead! So she does not have to see the pig-sick traitor her son has become”, I yelled.

These harsh words rolled off Dmitri’s smiling face like water from a monk's tonsure.

“The Tatar says you have until first light on the morrow to open the gates. Then the sack will begin.”

He strode back to the waiting army and disappeared among its throng.

Day 6

I spent the night scuttling about the castle consulting all who remained to be consulted. Despite my violent exhortations of the fate set to befall us, most were too weak to even bother to peek over the parapet.

To them, our fate had become merely illusory. An idea that could not be faced at this moment, something they would have to consider at a later date.

The one exception was Karl. Though his oozing legs caused him great pain, he yelled for troops to be rallied, for every man, woman and child to be equipped with sword or stone, for oil to be boiled, for arrows to be notched and sharpened.

I was momentarily inspired by his vigour, but as first light dawned I noticed the froth at his mouth and the wildness in his eyes and realised his will to fight was mostly madness.

“Bring me up to the castle wall!” Karl yelled. “I want to look upon the foul beasts that think they can breach this keep! They will learn thy name and by God they will fear it!”

Karl continued to rail and swear as I dragged him by his arms through the courtyard and thudding up the castle steps.

Halfway up the steps Karl’s lambasting suddenly ended. He was dead. But true to my word, I dragged his heavy corpse to the top of the wall and leaned his glass-eyed body beside an arrow-slit.

It was in this way, sweating with exertion with Karl’s corpse beside me, that I heard the first siege ladder straddle the wall. It landed with the clunk of wood on stone a short distance from me. I expected to hear a storm of further clunks, but I did not. It seemed this lone ladder would be enough for us.

I trotted to the edge of the wall and peered down. At the bottom of the ladder was a commotion of Tatars with long pikes, pressing a nervous soldier to climb. They laughed in their rhythmic way and did not seem much filled with hellfire. The reluctant soldier wept and wailed. He gripped the ladder’s base like a ship's mast in the high seas and could not be extricated from it no matter the kicks or prods he received.

One of the Tatars became frustrated at the farce and gave the soldier a mighty whack with the base of his pike. The soldier was knocked into the mud, picked up by the scruff of his tunic and forced up the ladder at the end of a pike-blade.

With a slow measured step, he began to journey upward. No other Tatars followed. They seemed to be leaving it to this soldier alone to sack the castle.

In an attempt to knock the climber from his reluctant perch I threw a heavy stone down the ladder. It crashed into him and knocked the hat from his head.

It was then that I saw that the Tatar was my cousin, Dmitri.

He looked frightened, more so even than I. The Tatars grew impatient and fired a few wayward arrows near Dmitri to speed things up. He picked up the pace and scuttled up the ladder.

I turned to the inner sanctum of the castle, “They are coming! The invasion has begun!” I yelled.

All was quiet.

Over the castle wall I looked down at Dmitri reaching the top of the ladder.

He looked plaintively at me as he attempted the clamber over the wall. “Wait wait wait wait wait wait wait!” He cried.

But I had endured weeks of waiting and was sick of it. I pushed him from the ladder and watched him fall to the ground below with a shriek, then a thud, then silence.

The Tatars laughed for a brief moment, then walked back to their lines and set their siege engines in motion.

Seeing nothing else for it, I went down and opened the gates.

Day 7

Having never seen a sack before I was a bit let down by it all. Sure there was murder and mayhem, thievery and destruction, but it all seemed a bit forced to me. Like a travelling actor who trots out their performance at village after village, and in this way loses the power of his tale.

True to Dmitri’s word the Tatars killed everyone but me. There weren't many to be killed, truth be told, and the Tatars were hard pressed to fill their bags of ears. Many set to the grim task of rifling through long deceased corpses to find half-decent ears to add to their trophies. But even this ghoulish task they did with a wariness that showed their heart was not really in it.

The be-hatted Tatar seemed pleased to finally see me up close. He slapped my cheeks in a jovial way, and had his men lift me onto a horse, and found great comedy with my inability to stay on with all its bucking and biting.

They spent the good part of the day carting the metalwork from the keep, and took much care with the linen, curtains, robes, and other instances of coloured cloth. They found a pile of chicken feathers and gave it to me with much ceremony like it was some great prize. This caused much laughter in the little general, who began referring to me as tak-ya, which I took to be their word for a hen.

Throughout all of this I found myself in a strange dream state. Nothing I saw or experienced seemed to be real. It was like watching my own life through murky water.

I watched myself as I was carted from castle to castle, as the Tatar host forced me to step up to the walls of my neighbours, as I dodged rocks and oil, and tried to force the surrender of my countrymen.

To my surprise, as the weeks passed I watched myself begin to excel at this task.

Something in my sardonic tone, or the grim matter of fact way I pointed out the hopeless situation of the besieged, allowed the Tatars to enter many castles through open gates.

I did not boast like Dmitri had done, or threaten, or cajole.

I simply expressed what had grown within my soul during the thirteen weeks of my own siege; a black feeling that pain, death and suffering was the natural way of the world - and I shared this feeling with those who still clung foolishly to hope.

I rode for some time with the Tatars, and in this way began to think of myself no longer as a baker, but a conqueror.

POST SCRIPT:

Currently listening to: Surface Tension by Annahstasia

Currently Reading: The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. I also just finished The Bee Sting by Paul Murray - so good, but no one told me how brutal this is - funny yes, but also f—ked up sad!

Currently watching: Too much tik tok.

If you want to support my music these are a few options:

Buy the album/merch from Bandcamp!

Share the songs with a friend who might be into it!

Follow me on Instagram